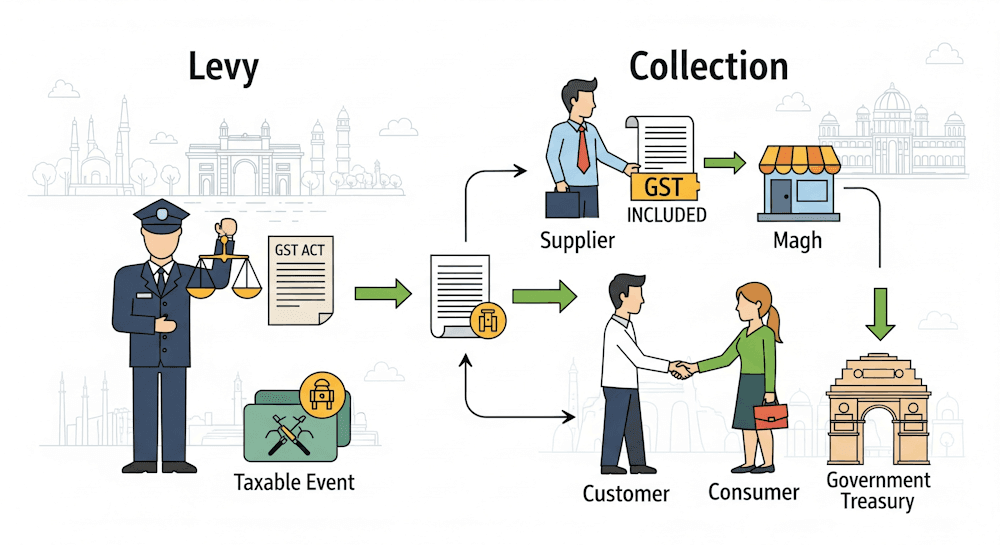

Okay, so let’s talk GST for a second. When it rolled out back in 2017, people were kind of confused. Some thought they’d have to stand in line at a government office and pay GST directly, like how you pay electricity bills. Others thought it was hidden somewhere in product prices and we wouldn’t even notice. The truth is in between, and that’s where two big terms come up: levy and collection.

They sound like heavy legal jargon, right? But honestly, levy just means the government saying, “We’re gonna tax this thing, and here’s the rate.” Collection is just “Okay, now here’s how we actually get the money.”

Let me break it down the way you’d explain it to a friend.

So, what’s levy anyway?

Levy is basically the government giving itself the legal green light. Without levy, no tax. With levy, yes tax. That’s it.

In GST, levy comes from Section 9 of the CGST Act, 2017. The law says: GST is levied on the supply of goods and services (but not everything—for example, alcohol for human use is left out).

Think of it like a traffic signal. Green light = go (this item is taxable). Red light = stop (not taxable). And depending on the product or service, the law decides the rate slab—0%, 5%, 12%, 18%, or 28%. That’s levy in action.

Collection – the part you actually feel

Now levy is all legal talk. Collection is where you actually see GST in your life. You buy something, you see GST on the bill. That’s collection. But here’s the thing—you don’t pay GST directly to the government (unless it’s a special case). You pay it to the seller, who then passes it along to the government later.

👉 Say you buy a shirt for ₹1,000. Add 5% GST and the bill becomes ₹1,050. You pay the shopkeeper ₹1,050. Out of this, he keeps ₹1,000 (his sale) and owes ₹50 to the government.

So the money travels like this: customer → seller → government. The seller is just the middleman, like a tax collector in disguise.

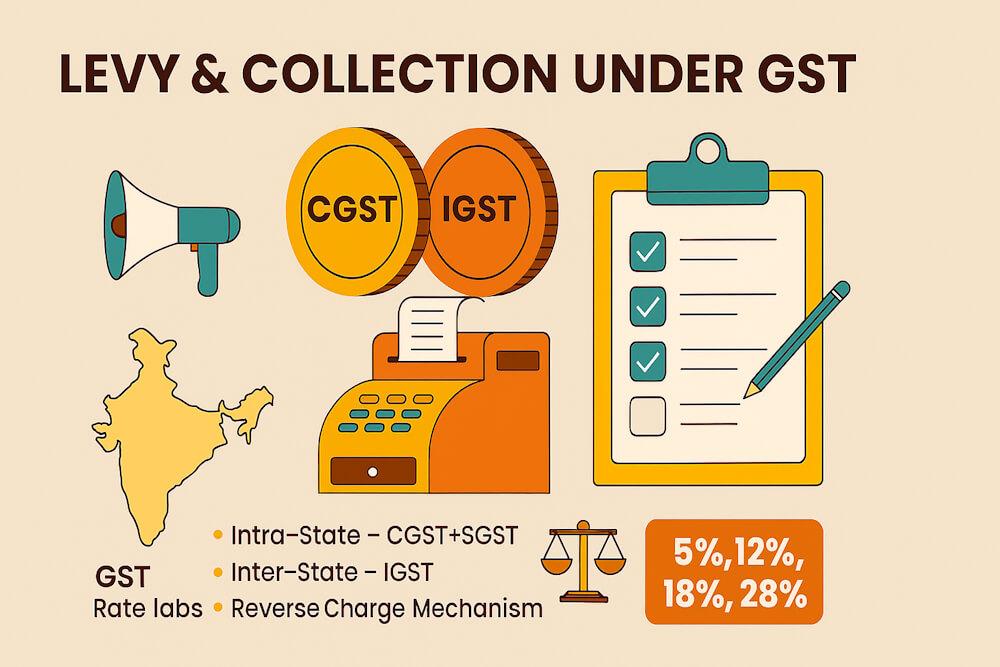

Why India made GST dual

Now here’s the twist. Because India is federal, both Centre and States want their share of taxes. To stop endless fighting, GST is split.

- CGST (Central GST) goes to the Centre.

- SGST (State GST) goes to the State, but only for supplies happening inside a state.

- UTGST (Union Territory GST) is the same idea but for UTs.

- IGST (Integrated GST) applies when goods/services move across states. Collected by the Centre, later shared with the consuming state.

👉 Example: You buy a fridge in Delhi from a Delhi shop → CGST + SGST. 👉 You order a fridge from Maharashtra and it’s delivered to Delhi → IGST.

It’s like splitting the same pizza. Sometimes you and your friend split it directly (CGST + SGST). Sometimes one person pays first and later shares (IGST).

The slabs – not one flat rate

Here’s where levy shows up again. GST isn’t flat. Different things fall into different slabs.

- 0% for essentials like milk.

- 5% or 12% for basics like packed food, clothes, medicines.

- 18% for most services (restaurants, telecom, etc.).

- 28% + cess for luxuries like cars, tobacco, aerated drinks.

So levy isn’t just “this gets taxed.” It’s also “how much gets taxed.”

The timing headache – time of supply

For businesses, knowing when GST applies is a big deal. That’s called the time of supply.

- For goods, it’s usually when you raise the invoice or deliver—whichever is earlier.

- For services, it’s when the service is provided or billed.

👉 Example: You raise an invoice on 1st May but deliver on 5th May. GST liability arises on 1st May itself.

Get this wrong, and you could end up paying late or paying twice.

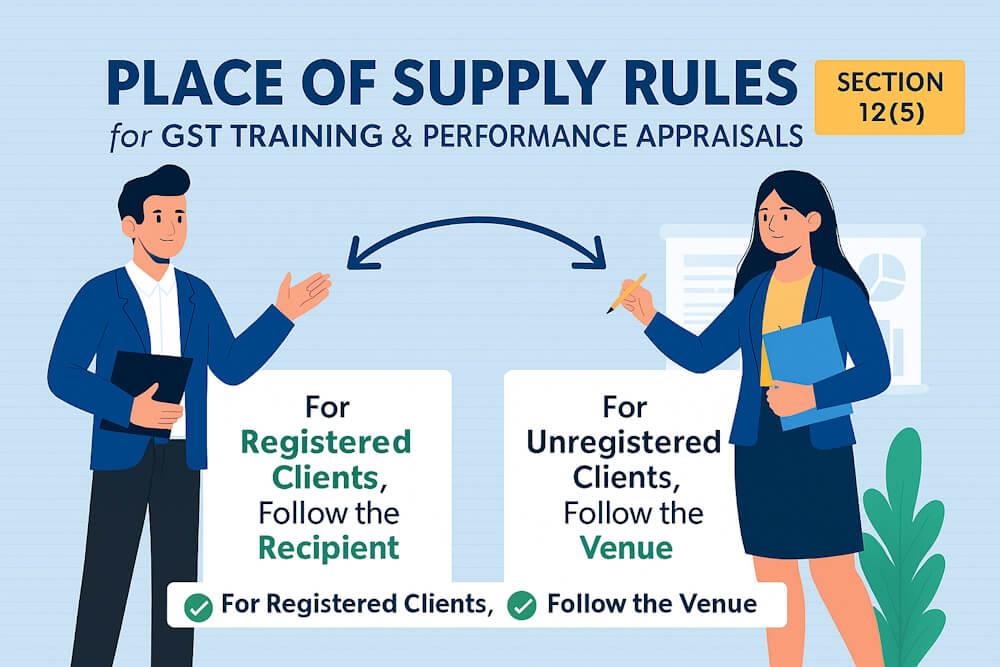

Place of supply – deciding who gets the tax

Another important piece is place of supply. This is what decides whether you charge CGST+SGST or IGST.

👉 A shop in Karnataka sells goods to a buyer also in Karnataka → CGST + SGST. 👉 The same shop sells to a buyer in Tamil Nadu → IGST.

This avoids states fighting over revenue. It’s the rule that says: whoever consumes it, that’s the state that gets the tax.

Reverse charge – when the buyer pays directly

Normally, the seller collects GST. But in some cases, the responsibility flips—it’s the reverse charge mechanism (RCM).

👉 Example: An Indian business hires a foreign consultant. Since the consultant isn’t registered under GST, the Indian buyer pays GST straight to the government.

This way, the government doesn’t lose out just because the supplier isn’t in India.

Not everything is taxable

Levy doesn’t mean tax on everything. Some goods and services are exempt. Like healthcare, education, fresh fruits, unprocessed cereals. These are left out deliberately so basic needs don’t get more expensive.

Why businesses care so much

For businesses, levy and collection aren’t “just theory.” They tell you:

- What rate to charge.

- Whether to apply CGST+SGST or IGST.

- When exactly liability kicks in.

- If reverse charge applies.

Mess this up, and you’re either paying too much tax or risking penalties.

And why even consumers should care

A lot of people think GST is just a headache for businesses. But honestly, as a consumer, once you get levy and collection, you suddenly understand why your bill looks the way it does.

That restaurant bill with CGST and SGST split in two lines? That’s levy + collection at work. That online order showing IGST? That’s because it’s interstate. And the best part—you also notice when something is exempt. Like if someone tries to charge GST on fresh fruits, you’ll know something’s fishy.

Wrapping up (kind of)

Levy and collection might sound like boring words, but they’re the backbone of GST. Levy decides what and how much to tax. Collection is the actual process of who pays and how the money moves to the government.

Once you see that, GST makes way more sense. Next time you see CGST, SGST, or IGST on a bill, you’ll know it’s not random—it’s the system doing its thing.

And honestly, that’s it. It’s not as scary as the legal language makes it sound. It’s just a big loop: government declares what’s taxable → you pay at the counter → seller passes it on → government pockets it. End of story.